Natural capital accounts show how natural resources contribute to the economy and how the economy affects natural resources. The accounts are an extension of the System of National Accounts. Natural capital accounting integrates natural resources and economic analysis, providing a broader picture of development progress than standard measures such as GDP.

This new series, "NCA in Action," shows how the accounts inform national policies and translate into action on the ground.

Australia’s water accounts inform policy to tackle impact of drought

When severe and prolonged drought hit Australia’s Murray Darling Basin, the country’s agricultural heartland, policymakers used economic modeling to weigh up the most efficient and cost effective policies to recover water and reduce consumption. Water supply and use tables from water accounts were central to these models.

The models presented clear evidence for a water buyback policy being the best to tackle the acute water shortages and limit the economic impact and environmental damage caused by the drought. Ultimately, for political reasons a different approach was adopted.

"By having access to the Australian Bureau of Statists' data on water supply and use, we were able to show that the impacts of buybacks are nothing like the ones associated with droughts. The data used constructed a strong argument,” said Professor Glyn Wittwer of the Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University.

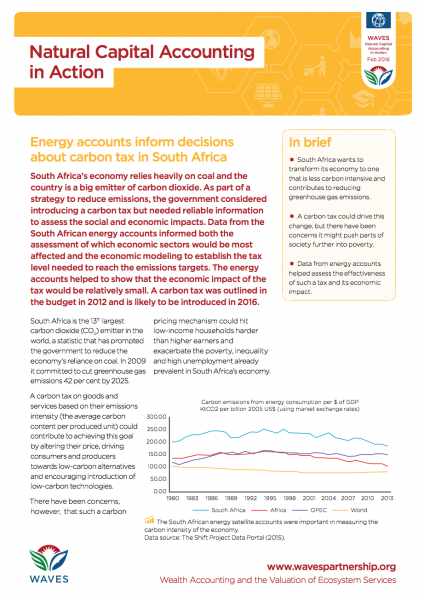

Energy accounts inform decisions about carbon tax in South Africa

South Africa is the 13th largest carbon dioxide (CO2) emitter in the world, a statistic that prompted the government to reduce the economy’s reliance on coal. In 2009 it committed to cut greenhouse gas emissions 42 percent by 2025.

In coming up with a strategy, the government considered introducing a carbon tax but needed reliable information to assess the social and economic impacts. Data from the South African energy accounts informed both the assessment of which economic sectors would be most affected and the economic modeling to establish the tax level needed to reach the emissions targets.

The energy accounts helped to show that the economic impact of the tax would be relatively small, and that a phased-in tax would achieve the national emissions targets set for 2025 while reducing GDP and employment by only 1 percent and 0.6 percent, respectively. A carbon tax was outlined in the budget in 2012 and is likely to be introduced in 2016.

Australia’s pilot ecosystem accounts benefit management of Great Barrier Reef

How do you manage an area as vast and complex as the Great Barrier Reef? Or any other landscape subject to different human pressures over time? The application of natural capital accounting and valuation methods to ecosystems and protected areas, currently being piloted in Australia, offers a useful framework to do this. It could provide systematic data, comparable over time, to improve the quality of decisions by protected area managers and political decision makers alike, in challenging development and climate change contexts.

A World Heritage Site, the reef is thought to provide a habitat for over 1,500 fish species, 133 varieties of sharks and rays, and more than 30 species of whales and dolphins. It is a significant magnet for international tourism, contributing more than AUD5 billion to the Australian economy each year and generating about 68,000 jobs. However, the health of this global treasure is declining and reef managers have been searching for ways to establish data monitoring systems to enhance management effectiveness.

"Ecosystem accounting allows for a more targeted management response. If we can quantify the drivers of degradation and pressures as much as possible, then we prevent things from happening, minimize impacts or maximize benefits for the community," said Margaret Gooch, manager of social and economic science, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Guatemala’s forest accounts link forest resources with the economy

Guatemala lost 40 per cent of its forest cover between 1950 and 2001. Concerns regarding the future of forests and the forestry sector prompted key government agencies, including the Central Bank working with the Rafael Landivar University, to begin constructing forest accounts in 2006, publishing them in 2009. Guatemala had a much higher rate of deforestation than elsewhere in Central America, and the accounts provided more than statistics on the issue. They made explicit the link between forest resources and the economy, as well as the cost of losing the country’s forests. The process, and the results, opened up a lively debate between the stakeholders involved, and informed national policies — such as on fuelwood use.

The accounts show how in 60 years Guatemala has gone from nearly 7 million hectares of forest to just 3.7 million — losing nearly half of its forests in a relatively short time. The added transparency in accounting also revealed the extent of non- controlled logging by private landowners, which takes place outside institutional regulatory frameworks and some of which is illegal. It also revealed households’ high dependence on fuelwood: 64 per cent of the population, for example, relies on fuelwood for their main source of energy — two thirds of that number in rural areas.

"The Forestry Enterprises Electronic Systems (SEINEFF) is an example of how information from the forest accounts has been used. This online platform provides trusted, up-to-date information on legal forestry products to promote legal marketing and trade," said Jaime Luis Carrera, Institute of Agriculture, Natural Resources, and the Environment (IARNA).

Sweden’s carbon accounting informs its carbon tax policy

As Swedish policymakers put together a climate bill,they relied on economic models to pinpoint policies that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions while minimizing costs to GDP, employment and growth. At the heart of this analysis was Sweden’s sector-by-sector accounting of CO2 emissions and energy use, in parallel with standard economic accounts.The emissions and energy accounts enabled detailed modeling of alternative proposals, which led to a finely tuned policy package with significant cost savings.

The legislation, now in effect, promises that greenhouse gas emissions from part of the economy in 2020 will be 40 per cent below 1990 levels. So far, emissions have fallen by 10 megatons annually, around half of the reduction needed to reach the target. And the same CO2 and energy accounts that shaped Sweden’s climate plan will also help keep it on track. Economic projections from the National Institute of Economic Research (NIER)’s model are used by other Swedish agencies to produce regular forecasts of energy use and emissions.

"The emissions accounts are very useful in our daily work. Our model [based on the accounts] is used in most climate policy analyses commissioned by the government," said Eva Samakovlis, head of research for NIER.